Patients as knowledge collaborators: From care recipients to drivers of change

Author: Dr Sandrine Ding1,2

- 1. HESAV School of Health Sciences – Vaud

- 2. BEST: A JBI Centre of Excellence, Switzerland

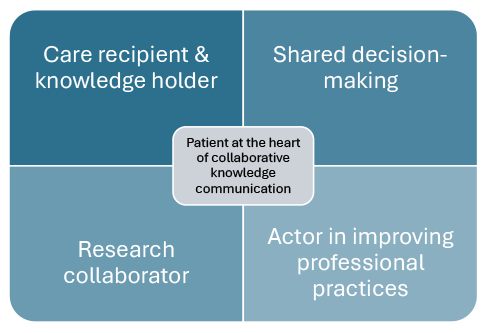

At the very heart of healthcare are patients, for whom treatments, information and advice are shaped to fit their unique clinical realities. Patients are not merely passive recipients of care; they are holders of valuable knowledge. For instance, people living with chronic illness develop a deep understanding of their condition, including symptoms and their management. This experiential knowledge is crucial for tailoring care, improving communication and supporting more personalised management.

Yet, the patient’s role is not limited to reporting essential clinical information (e.g. symptoms, allergies, lifestyle habits); they are an active partner in the care process. This empowered role is expressed through shared decision-making, a process that actively involves patients in therapeutic choices by integrating their values, priorities and life goals. Shared decision-making is also a fundamental pillar of evidence-based practice, which brings together three elements: the best available scientific evidence, clinical expertise, and patient preferences and beliefs. Thus, shared decision-making embodies patient involvement in evidence-based practice.

Patients' in-depth knowledge extends far beyond the scope of the individual clinical relationship mentioned above. In the field of health research, patients now occupy a strategic position: they participate in defining research priorities, designing studies and even disseminating results. Their partnership is also expected, particularly in the process of synthesising evidence. Methodological guides and frameworks have been published to facilitate this involvement. For example:

- Principles have been proposed for consumer engagement in systematic reviews,

- The GIN public toolkit provides recommendations for their participation in guideline development, and

- Innovative approaches are being developed for consumer involvement in the synthesis of living evidence and the development of living guidelines.

Patients as key actors in changing professional practice

The aim of evidence synthesis – as promoted by organisations such as JBI or Cochrane – is to make scientific data more accessible and usable. Yet the availability of evidence syntheses is not enough; to change clinical practice, implementation support is required.

This is the role of implementation science, which seeks to bridge the research–practice gap. Theories, models and frameworks developed in this field provide structured approaches to professional practice change by identifying determinants of innovation adoption, outlining stages of implementation and defining outcomes of implementation.

Although patient, caregiver and public involvement is now recognised as best practice in health research, patients’ participation in the co-design and co-conduct of implementation projects remains limited, partly due to a lack of practical guidance for researchers.

Among the strategies aimed at improving professional practice, one explicitly recognises patients as key collaborators, whereby patients are considered mediators of the intervention. This strategy, known as patient-mediated interventions, is defined as ‘any intervention aimed at changing the performance of healthcare professionals through interactions with patients, or information provided by or to patients.’

Evidence suggests that patient-mediated interventions could improve practice by increasing healthcare professionals’ adherence to clinical recommendations and practice guidelines. They facilitate innovation implementation in two main ways:

- Patient-reported health information: When patients actively share data about their health status and needs, professionals are more likely to provide care aligned with relevant recommendations.

- Patient education: When patients are given training or advice regarding their condition or treatment, they are empowered to take an active role in their care, influencing the quality of care they receive.

While patient-mediated interventions act primarily at a single stage of the implementation process, patient involvement should ideally be embedded throughout all stages – from defining which clinical practice needs improvement for instance, to selecting strategies or to co-developing indicators. They can thus co-define clinical quality indicators with healthcare professionals, based on existing recommendations. For example, in an oncology context, patients with head and neck cancer collaborated with a multidisciplinary team (otorhinolaryngologists, surgeons, oncologists, nurses, radiation therapists, physiotherapists, dieticians and oral hygienists) to co-define quality-of-care indicators. This aligned clinical priorities with patient expectations and improved the relevance of the chosen indicators.

Tools and frameworks to support patient involvement in implementation

Despite these benefits, patient integration in knowledge translation remains limited. This may be linked to a lack of training or confidence among professionals on how to engage patients effectively. Several initiatives have emerged to address this:

- Consumer Voice provides slides, audiovisual content and templates to facilitate patient engagement in practice-change strategy development. Although originally designed for suicide prevention, these tools are adaptable to other clinical contexts.

- Guiding principles are also being developed to support the participation of patients, caregivers, service users and the public in the overall process of implementing evidence in health and social service practice. These principles are being developed as part of the Pathways to Implementation for Public Engagement in Research (PIPER) project.

- Living labs represent an innovative approach. These community-integrated co-design platforms bring patients and families together with researchers and clinicians throughout the entire research process: from study design to research execution and translation into practice. They are developing notably in the fields of mental health and paediatric rehabilitation.

Key take-home messages

The active involvement of patients in healthcare and health research, including the synthesis of evidence, shows that they are considered true collaborators and knowledge holders. Patient-mediated interventions and their engagement in defining clinical indicators illustrate their impact in translating scientific evidence into practice.

The challenge now is to normalise this involvement at every stage of the knowledge transfer process, so that patient perspectives shape priorities, process and implementation outcomes. New tools and frameworks can support healthcare professionals in integrating patients’ perspectives into the transfer of knowledge into practice in a systematic and sustainable manner. This shift would not only lead to better quality and relevance of care and services but also strengthen patient empowerment. By ensuring that the real needs and values of the population are met, this approach can help improve trust in science and the healthcare system.

References

Archibald, M. M., Akinwale, O., Hammond, E., Mora, A., Woodgate, R. L., & Wittmeier, K. (2024). A Living Lab for family-centered knowledge exchange in pediatric rehabilitation and development research: a study protocol. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 23, 16094069241244866. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069241244866

Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). (2021). EPOC Taxonomy. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.5105850

Elwyn, G., Cochran, N., & Pignone, M. (2017). Shared decision-making—the importance of diagnosing preferences. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(9), 1239. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1923

Fønhus, M. S., Dalsbø, T. K., Johansen, M., Fretheim, A., Skirbekk, H., & Flottorp, S. A. (2018). Patient-mediated interventions to improve professional practice. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2018(9). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012472.pub2

GIN Public Toolkit: (n.d.). GIN. Retrieved 20 September 2025, from https://g-i-n.net/toolkit

Malterud, K., & Elvbakken, K. T. (2020). Patients participating as co-researchers in health research: A systematic review of outcomes and experiences. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 48(6), 617–628. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494819863514

Mathieson, A., Brunton, L., & Wilson, P. M. (2025). The use of patient and public involvement and engagement in the design and conduct of implementation research: A scoping review. Implementation Science Communications, 6(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-025-00725-w

Palmer, V. J., Bibb, J., Lewis, M., Densley, K., Kritharidis, R., Dettmann, E., Sheehan, P., Daniell, A., Harding, B., Schipp, T., Dost, N., & McDonald, G. (2023). A co-design living labs philosophy of practice for end-to-end research design to translation with people with lived-experience of mental ill-health and carer/family and kinship groups. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1206620. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1206620

Pathways to Implementation for Public Engagement in Research. (n.d.). Retrieved 21 September 2025, from https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/med/research/hscience/sssh/research/piper/

Pollock, A., Campbell, P., Struthers, C., Synnot, A., Nunn, J., Hill, S., Goodare, H., Morris, J., Watts, C., & Morley, R. (2019). Development of the ACTIVE framework to describe stakeholder involvement in systematic reviews. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 24(4), 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819619841647

Porritt, K., McArthur, A., Lockwood, C., & Munn, Z. (2023). JBI’s approach to evidence implementation: A 7-phase process model to support and guide getting evidence into practice. JBI Evidence Implementation, 21(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000361

Staniszewska, S., Walsh, J., Langley, J., Dziedzic, K., Moult, A. Andrews, N., Bain, C., Bearne, L., Bird, P., Gazeley, T., Grant, R., Hickey, G., Luff, R., Rycroft-Malone, J., Seers, K., Skrybant, M., Stacey, D., Swaithes, L., & Rasburn, M. (2025). Developing a role for patients and the public in the implementation of health and social care research evidence into practice: The PIPER study (Pathways to Implementation for Public Engagement in Research) realist evaluation protocol. Research Involvement and Engagement, 11(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-025-00728-w

Synnot, A., Hill, K., Davey, J., English, K., Whittle, S. L., Buchbinder, R., May, S., White, H., Meredith, A., Horton, E., Randall, R., Patel, A., O’Brien, S., & Turner, T. (2023). Methods for living guidelines: Early guidance based on practical experience. Paper 2: consumer engagement in living guidelines. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 155, 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.12.020

Synnot, A., Weeks, L., Hill, S. J., Lytvyn, L., Radar, T., Randall, R., Morley, R., Jaure, A., Elliott, J. H., & Turner, T. (2024). Consumer engagement in living evidence “a beautiful opportunity”: International qualitative study with patients and methodologists. Clinical and Public Health Guidelines, 1(4), e70002. https://doi.org/10.1002/gin2.70002

Van Overveld, L. F. J., Braspenning, J. C. C., & Hermens, R. P. M. G. (2017). Quality indicators of integrated care for patients with head and neck cancer. Clinical Otolaryngology, 42(2), 322–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.12724

Woodward, E. N., Ball, I. A., Willging, C., Singh, R. S., Scanlon, C., Cluck, D., Drummond, K. L., Landes, S. J., Hausmann, L. R. M., & Kirchner, J. E. (2023). Increasing consumer engagement: Tools to engage service users in quality improvement or implementation efforts. Frontiers in Health Services, 3, 1124290. https://doi.org/10.3389/frhs.2023.1124290

To link to this article - DOI: https://doi.org/10.70253/GLLN4109

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this World EBHC Day Blog, as well as any errors or omissions, are the sole responsibility of the author and do not represent the views of the World EBHC Day Steering Committee, Official Partners or Sponsors; nor does it imply endorsement by the aforementioned parties.