Implementing kangaroo mother care to reduce neonatal mortality

James Temop works as a clinical research assistant in the Division of Health Science at the University of Goroka, Papua New Guinea. In this role, he works closely with nursing and midwifery students who receive clinical skills training at the Goroka Provincial Hospital. One of the main concerns of the hospital, and Papua New Guinea in general, is the high incidence of newborn deaths.

‘Infants born before term or at low birth weight are at an increased risk of morbidity and mortality, disrupted growth and development, and are likely to develop chronic disease’, says James. ‘Lack of cost-effective interventions here contributes to the number of neonatal deaths.’

In 2017, the neonatal mortality rate for Papua New Guinea was 23.7 deaths per 1000 live births (World Data Atlas), which was the highest in the Oceania region. In 2018, the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) introduced a program in Papua New Guinea aiming to reduce the rate of newborn deaths. Goroka Provincial Hospital was one of the sites that implemented the program.

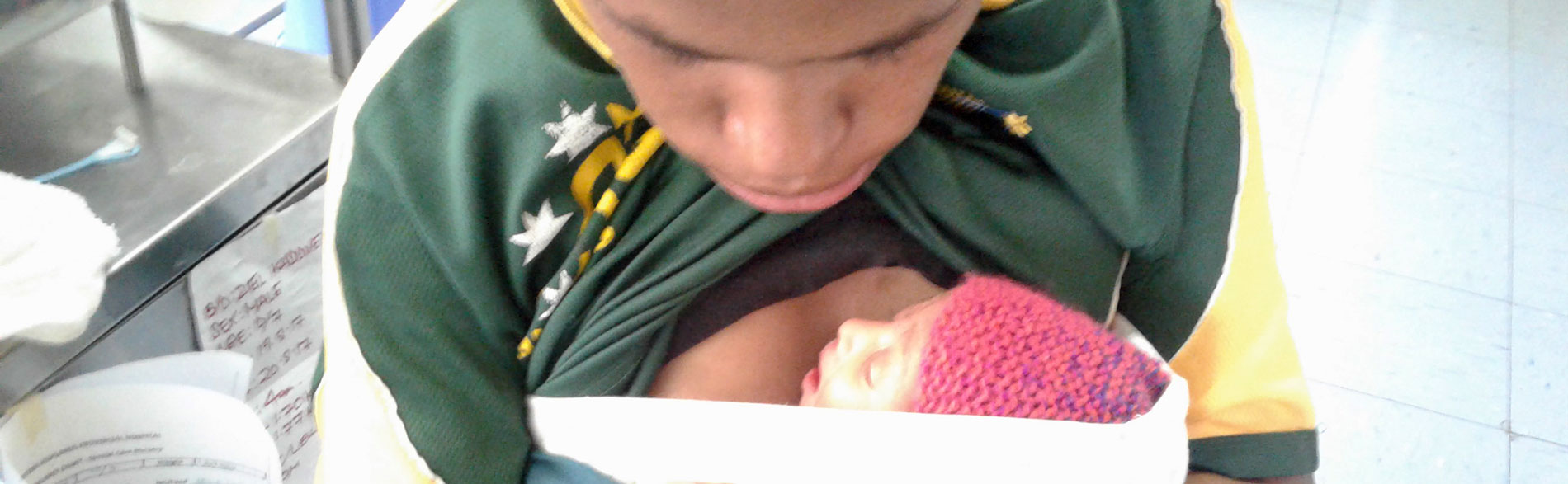

James was sponsored to participate in the Evidence Implementation Training Program in Adelaide to learn about evidence-based healthcare and to develop the skills and knowledge necessary for leading practice change at Goroka Provincial Hospital. As part of the program, James led an evidence implementation project that focused on a specific intervention, kangaroo mother care, for improving the outcomes of preterm and low birth weight newborns. ‘Kangaroo mother care simply involves skin-to-skin contact, chest-to-chest, with a parent – usually the mother’, explains James.

Kangaroo mother care has proven effectiveness and is a practical, easy-to-use method for helping to prevent infant deaths. Given that Papua New Guinea has limited resources, kangaroo mother care is an ideal intervention to implement.

The UNICEF program that was introduced at Goroka Provincial Hospital in 2018 included training for mothers on how to perform kangaroo mother care, but even though organisational policy supported the implementation of kangaroo mother care, the practice was not adopted across the hospital.

Indeed, a baseline audit to examine the practice of the intervention found that less than 30% of mothers performed kangaroo mother care. Further, only 20% of healthcare staff received education on kangaroo mother care and only around 25% of mothers received education about it. Regular assessment and documentation of infants’ condition by healthcare staff was very poor.

‘We were disappointed with these results, so we consulted with nursing, midwifery and community health staff to inform them of the results and to gather their perspectives. This strategy of consulting with staff not only provided us with valuable information, but also helped to create a sense of ownership of the project by staff as we worked together to improve compliance for better health outcomes for newborns’, says James.

Informed by the feedback provided by staff, James and his team developed resources for parents and for healthcare practitioners, such as handouts and posters, and education programs to increase knowledge and improve the adoption of kangaroo mother care.

Training programs for all relevant staff were piloted and refined by midwifery tutors from Goroka University. ‘I was very fortunate to work with a team of academics and nursing/midwifery students from the university, and nursing staff from rural health centres who unselfishly and tirelessly shared their knowledge and skills in making the project successful’, says James.

However, initially, not all staff were enthusiastic about being involved and some appeared to lack interest in the project. In response, James and his team continued to communicate the importance of the project, consult with staff, and involve them in the testing of educational resources and materials. ‘We also highlighted to staff that the project was being facilitated by JBI. Everyone considers JBI one of the leading organisations in evidence-based healthcare and as very reputable. This made staff feel privileged to be a part of the project’, says James.

Improving the staff’s understanding of the project’s importance and the concept of evidence-based healthcare was important in overcoming challenges to practice change. ‘Sociocultural norms and adherence to traditional newborn practices were difficult to change at first, even after training’, says James. ‘The ongoing communication and consultation with staff to keep them informed, educated and motivated assisted in achieving widespread change in practice and in the organisation’s culture.’

A follow-up audit found that improvements in the knowledge and practice of kangaroo mother care had been achieved by parents and hospital staff. For example, results indicated a 70% increase in staff receiving education for the implementation of kangaroo mother care. Results showed 100% of parents received education on the benefits of kangaroo mother care for their low birth weight infant, an increase of 75% from the baseline audit.

Importantly, the audit results indicated an increase in instances of kangaroo mother care following birth, or as soon as the infant’s condition permitted, from less than 30% to 90%.

The project resulted in a significant increase in the adoption of kangaroo mother care by not only mothers, but also fathers. ‘The project was successful in engaging with fathers and increasing their involvement in the care of their babies. This was one of the highlights of the project’, says James.

The project also achieved improvements in the assessment and documentation practices of neonatal patients by hospital staff. Compliance with assessing, undertaking observations and position checks of neonatal patients increased by 60%, and documentation of neonatal patients’ condition increased by 75%.

The positive changes that were demonstrated in the follow-up audit prove that evidence-based healthcare can be low-cost and implemented successfully with limited resources. The project has also demonstrated the importance of continued communication and collaboration with key stakeholders to help ensure its success.

The challenge for James now is to help sustain the shift in organisational culture and practice in order to improve the care of infants, particularly preterm and low birth weight babies.

‘The project is ongoing’, says James. ‘The plan is to continue conducting clinical audits and to regularly offer the educational programs to relevant healthcare staff, so that they in turn can educate the parents.’

To assist in the sustainability of the project, James and his team have had discussions with the Division of Health Science at the University of Goroka to integrate the teaching of evidence-based healthcare and practices into the curriculum for midwifery and nursing undergraduate students.

The team’s journey towards zero deaths in infants has just started, and they are optimistic that with their dedication to evidence-based practice and strong partnerships, they will be able to achieve this vision in the near future.

Further resources

JBI Manual for Evidence Implementation (for GRiP approach)

Author

James Temop, University of Goroka

Disclaimers

Republished with permission from JBI jbi.global/our-impact/KMC

The views expressed in this this World EBHC Day Impact Story, as well as any errors or omissions, are the sole responsibility of the author and do not represent the views of the World EBHC Day Steering Committee, Official Partners or Sponsors; nor does it imply endorsement by the aforementioned parties.