Reducing maternal and neonatal deaths by improving quality of care during labour

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), almost all maternal deaths during pregnancy, delivery or within 42 days of childbirth occur in low-resource settings, and most could have been prevented. Likewise, the rate of neonatal mortality is disproportionately high in low- and middle-income countries. The majority of neonatal deaths are due to preventable causes such as pre-term birth complications, complications during labour and delivery, and infectious diseases such as sepsis.

Cameroon is one of the countries with the highest maternal and neonatal mortality rates. Dr Valery Nji implemented evidence-based strategies to improve the quality of care during labour in order to reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.

‘The World Health Organization provides guidelines for intrapartum care for every woman presenting in labour, but there is little or no compliance in resource-limited settings, mainly due to limited access to these guidelines. Instead, workplace culture and established practice guide the care of these women.’

Valery was sponsored by JBI to participate in the Evidence Implementation Training Program and to work closely with JBI research fellows to develop an evidence-based project to identify and implement best practice in the management of pregnant women in labour.

At the time, Valery was based at Bali District Hospital, but a two-month strike by doctors demanding better working conditions and pay threatened the project’s viability. The strike occurred at a time of political crisis: Anglophone territories in Cameroon’s northwest and southwest were declaring independence, and both the military and armed separatists were staging attacks on hospitals, which left medical professionals concerned for their safety.

Staff were transferred to St Blaise Catholic Hospital, a mission hospital in rural Cameroon, and the evidence implementation project re-commenced with a clinical audit to determine compliance. Criteria for the baseline audit were developed from WHO intrapartum care guidelines, which include non-clinical aspects such as effective communication, respectful care and labour companionship.

‘Intrapartum care models that place the healthcare provider as the sole decision-maker in the birth process may expose pregnant women to unnecessary clinical interventions that negatively impact a woman’s childbirth experience. By involving women in the decision-making process, taking into account their preferences and integrating their decisions with clinical experience and best available evidence, a woman’s child-birthing experience can be a positive experience.’

Indeed, the WHO framework emphasises that the experience of care is as important as the provision of clinical care for improving quality of care for pregnant women during childbirth.

‘Maltreatment of women during labour, be it physical or a failure to reach professional standards of care, is common in resource-limited settings. Developing and implementing a model of provision of continuous support to women during labour will improve outcomes for women and neonates, and decrease negative feelings about the childbirth experience’, says Valery.

Results of the baseline audit revealed that six of the 19 evidence-based criteria showed less than 60% compliance. Two criteria in particular showed low compliance:

• Criterion 9: Healthy pregnant women requesting pain relief during labour should be offered pain relief medications (0%)

• Criterion 15: Delayed umbilical cord clamping (not earlier than one minute after birth; 6%)

‘The result of 0% compliance against criterion 9 is due to the traditional belief that pains in labour are normal, and that women need no additional pain relief medications. The low compliance rate for criterion 15 is associated with the fear of intrapartum spread of HIV from a woman to her baby. This is despite no evidence showing that early cord clamping reduces the transmission of HIV’, says Valery.

Following the audit results, the team used the Getting Research into Practice (GRiP) framework to identify and assess barriers to evidence implementation, as well as strategies and resources required to overcome those barriers.

One of the barriers Valery encountered was the lack of cooperation from staff at St Blaise Catholic Hospital: ‘Workplace culture and staff generally being averse to adopting new practices posed challenges.’ To address those challenges, a multi-pronged strategy was employed that included educating staff on best practice, and explaining the existing gaps between current practice and evidence-based practice. Staff were then encouraged to engage in the project to gain technical expertise through training, and as an added incentive, staff actively participating in the project were given a financial stipend.

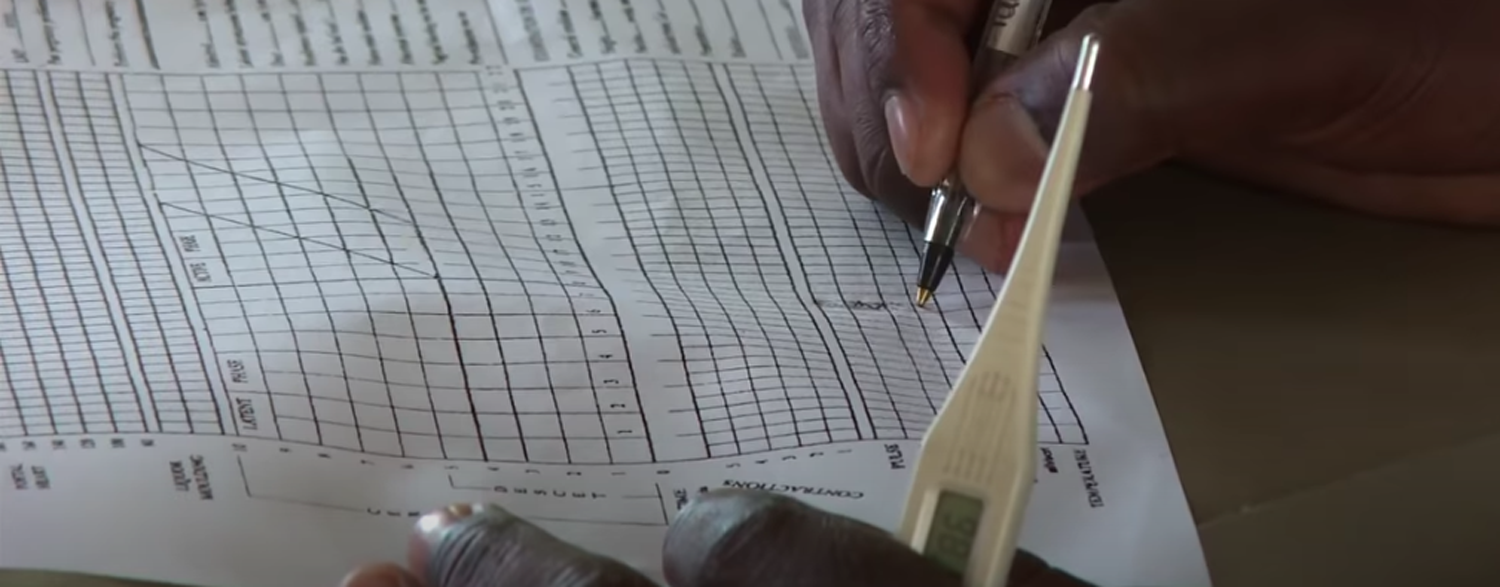

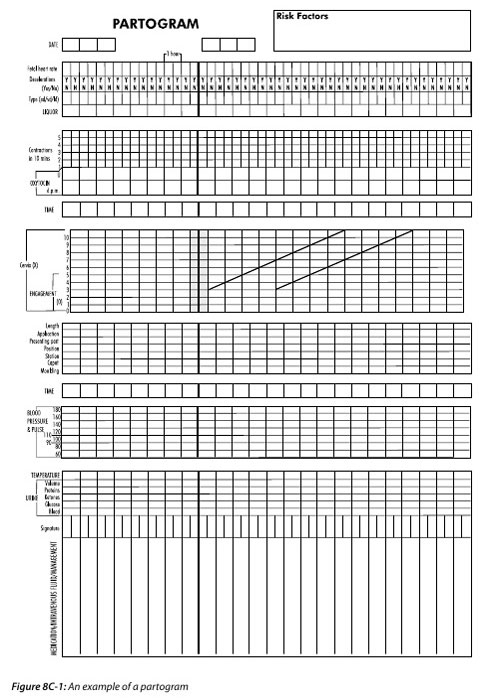

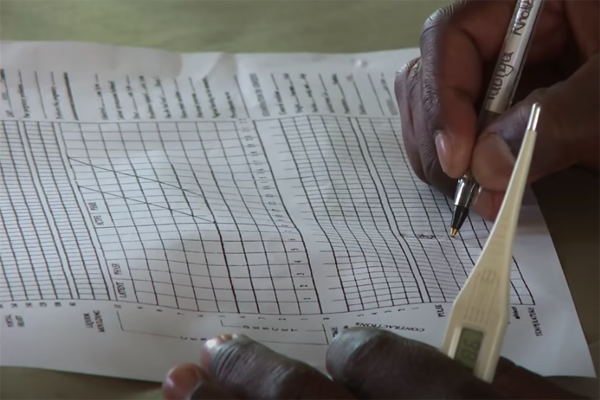

Technical expertise gained by staff as a result of the evidence implementation project included training on the use of the partogram. The partogram is an essential tool that helps clinicians detect abnormal progress of labour, foetal distress and signs that the mother is in difficulty.

‘Management of women in labour requires a complete understanding of the mechanisms of labour, a knowledge of medications, and the rationale for labour interventions. It also involves knowing how to use the partogram. The clinical audit revealed that most practitioners had inadequate knowledge on the current evidence-based guidelines in the management of women in labour. Therefore, the strategies implemented were directed towards improving the knowledge of the midwives to comply with evidence-based criteria, which included a practical training session on use of the partogram to monitor labour. Guidelines were developed and the project team made sure midwives were aware of, and had easy access to, those guidelines’, explains Valery.

‘During the baseline audit, 13 out of 19 criteria had a compliance rate greater than 60%. Six months post implementation of the project, 14 of these criteria attained 100%.’ Compliance also improved from 0% to 63% for criterion 9, and from 6% to 95% for criterion 15.

One audit criterion, however, decreased in compliance: Criterion 1: Effective communication, and respectful maternity care between maternity care providers and women in labour. Compliance decreased from the baseline value of 85% compliance to 50%. ‘Follow-up data for criterion 1 were collected from pregnant women after delivery, whereas in the baseline audit, data were collected from the midwives. This shows that while the midwives believe they are communicating effectively, their patients think otherwise. The patients wanted to be better informed by midwives about their health throughout their pregnancy and during labour’, says Valery.

The project’s future is one of continuous improvement. For example, education strategies for midwives will be reviewed, improved and evaluated to help ensure patients’ communication needs are met. Compliance against all guideline criteria will be audited every six months. Future directions for the project also include expanding beyond St Blaise Catholic Hospital to the greater district so that compliance against evidence-based guidelines informs broader policy. In addition, traditional birth attendants will be encouraged to engage in evidence-based practice and be educated on current guidelines.

‘The lack of access to evidence-based criteria by clinicians is especially low in resource-limited settings. This project demonstrates that the non-adherence to evidence-based guidelines which improve maternal and neo-natal mortality and morbidity, and improve the birth experience for women, is a result of limited access to evidence. We successfully improved compliance by making the guidelines available and easily accessed, and by educating clinicians on these guidelines.’

Further Resources

JBI Manual for Evidence Implementation (for GRiP approach)

Author

Valery Nji

Disclaimers

The views expressed in this this World EBHC Day Impact Story, as well as any errors or omissions, are the sole responsibility of the author and do not represent the views of the World EBHC Day Steering Committee, Official Partners or Sponsors; nor does it imply endorsement by the aforementioned parties.