We need to embrace nature’s complexity for disease prevention

Authors: Professor Robyn Alders and Professor Dirk Pfeiffer

COVID-19 reminded the world of the interconnectedness of human and animal health.

When a wild animal in a Chinese seafood market became suspect number one in the search for the source of the virus behind the pandemic, it was a wake-up call to many working in public health.

Understanding the interconnection between animal and human health is integral to One Health. This approach recognises that the health of humans, wild and domesticated animals, plants, the environment and ecosystems are all interdependent, so a multisectoral and interdisciplinary approach is required to achieve optimal health for all.

Some say this holistic understanding of health goes back to Hippocrates, or even further back, given that indigenous peoples have recognised that human health is inseparable from environmental health for thousands of years. However, it is only in recent years that the One Health approach has gained significant momentum.

Increasing collaboration between human and animal health researchers in the field of infectious diseases has become especially critical as the actions of people continue to create conditions ripe for pathogens to jump from one species to another. Using diverse types of evidence to inform policy and interventions to prevent and control future disease outbreaks, including pandemics, is essential.

Recent decades have seen a spate of major infectious disease outbreaks emerging and spreading from wild animals and livestock, such as H5N1 avian influenza (bird flu), SARS, H1N1 swine influenza (swine flu), MERS, H7N9 avian influenza, Ebola, Zika and COVID-19.

The global resurgence of avian influenza and its spillover to mammals is the most recent reminder that it is essential to get a broader picture of zoonoses (diseases that spread from animals to people) if we are to identify the risk factors for disease emergence and spread. The more we can break down the barriers between the natural sciences, the better.

However, the full picture remains elusive if we stop there. With a natural sciences–only perspective, the pathogen remains the sole focus. Yet, people’s behaviours, belief systems, knowledge and understandings also affect the risk factors and patterns of zoonoses – and we ignore these factors at our peril. That means including important political, socioeconomic, cultural and anthropological perspectives into zoonoses research.

As two senior natural scientists, we might not seem the most obvious beaters of the social science drum. However, our work in interdisciplinary projects, most recently the GCRF One Health Poultry Hub, makes us such.

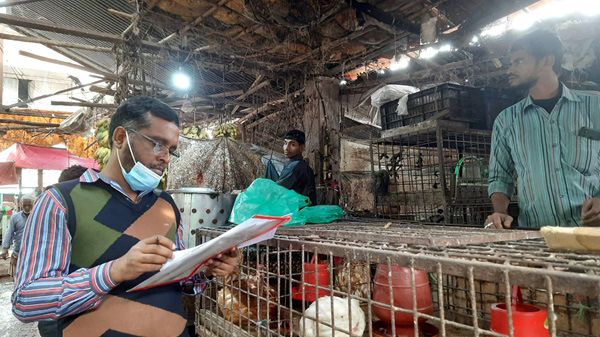

The One Health Poultry Hub is a large, multicountry interdisciplinary program researching how to minimise the public health risks associated with poultry intensification. Findings from the Hub illustrate the critical role of social science in zoonoses research; for example, in Bangladesh and Vietnam, where poultry intensification is rapid, avian influenza outbreaks in flocks are common and the threat of avian influenza virus (AIV) spillover to people is a constant threat.

In one area in Vietnam, biological sampling showed the widespread occurrence of AIV: one in five chickens sampled in markets and slaughtering facilities tested positive for AIV. However, it was the qualitative social science work (interviews with scores of farmers, traders, slaughterhouse workers and others in the supply chain) that revealed (among other things) that it is the high volatility of chicken market prices that presents a significant barrier to implementing realistic, sustainable and effective biosecurity on poultry farms.

Market volatility threatens farm profits and leads farmers to prioritise short-term goals to keep their business afloat over longer-term ambitions. This means farmers react when disease issues arise, rather than adopt preventive measures to keep disease at bay. Action to stabilise chicken prices and protect farmers against market volatility in Vietnam may be more effective in the long run in preventing AIV outbreaks than any traditional disease prevention approach.

Similarly, in Bangladesh, attempts to control AIV in the past have proved unsuccessful, in large part because measures have failed to address some everyday harsh realities for poultry farmers and traders. It was social science evidence that demonstrated that factors such as a lack of financial capital; unfavourable credit systems; limited access to economic information and veterinary expertise; and fluctuating costs for feed, chicks and medicines can influence the decisions made by people raising and trading poultry.

The result: again, farmers find themselves discouraged from investing in better hygiene measures, such as foot baths. They can even be pushed into adopting trading practices that are risky for disease transmission, such as selling sick chickens. Fortunately, in Bangladesh, steps are now being taken to consider the implications of such findings in new AIV prevention policies.

Working alongside social scientists on zoonoses research projects persuades us of the importance of One Health research. One Health doesn’t end with adding social sciences, of course. The role of environmental and ecosystem researchers and others is essential, including the modellers who can often help us piece available evidence together, and allow evaluation of possible interventions.

This makes zoonoses research highly complex and challenging. But nature is complex, and it doesn’t respect the sectoral and disciplinary boundaries that humans have erected. Only by embracing the complexity and the challenges of evidence collection will we move forward with One Health and its implementation, and take strides in the quest for improved health for all.

Take-home messages

- One Health is an approach that recognises that the health of humans, wild and domesticated animals, plants, the environment and ecosystems are interdependent.

- It is insufficient to focus on the linear biological risk factors behind disease emergence and spread. Instead, a complex systems approach needs to be adopted that acknowledges the multitude of other direct and indirect effects, such as people’s behaviours, belief systems, knowledge and understandings, as well as the political economy.

- Social science is integral to zoonoses research aimed at informing policy and interventions for disease control and prevention.

Bibliography

Dalton J. Coronavirus: Timeline of pandemics and other viruses that humans caught by interacting with animals [internet]. The Independent; 2020, April 27. Available from: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/coronavirus-pandemic-viruses-animals-bird-swine-flu-sars-mers-ebola-zika-a9483211.html

Greenwood M, Lindsay NM. A commentary on land, health, and Indigenous knowledge(s). Glob Health Prom. 2019;26(3_suppl):82-6.

Hassan MM, Dutta P, Islam MM, Ahaduzzaman M, Chakma S, Islam A, et al. The One Health epidemiology of avian influenza infection in Bangladesh: Lessons learned from the past 15 years. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2023;70(6):6981327.

Hippocrates. On airs, waters, and places (Adams F, trans.) [internet]. The Internet Classics Archive; n.d. Available from: http://classics.mit.edu/Hippocrates/airwatpl.html

One Health High-Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP), Adisasmito WB, Almuhairi S, Behravesh CB, Bilivogui P, Bukachi SA, et al. One Health: A new definition for a sustainable and healthy future. PLOS Path. 2022;18(6):e1010537.

One Health Poultry Hub. Pandemic prevention and preparedness in Bangladesh [internet]. One Health Poultry Hub; n.d. Available from: https://www.onehealthpoultry.org/impact-stories/pandemic-prevention-and-preparedness-in-bangladesh/

One Health Poultry Hub. Our Hub [internet]. One Health Poultry Hub; 2024. Available from: https://www.onehealthpoultry.org/about-us/our-project/

One Health Poultry Hub. Hub findings support a more holistic approach to public health in Vietnam [internet]. One Health Poultry Hub; 2023. Available from: https://www.onehealthpoultry.org/news/hub-findings-support-a-more-holistic-approach-to-public-health-in-vietnam/

One Health Poultry Hub. Biosecurity: Protecting poultry, people and profits [internet]. One Health Poultry Hub; 2024. Available from: https://www.onehealthpoultry.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Biosecurity_English_19.3.24_FINAL_compressed.pdf

Pinotti F, Kohnle L, Lourenço J, Gupta S, Hoque MA, Mahmud R, et al. Modelling the transmission dynamics of H9N2 avian influenza viruses in a live bird market. Nature Comm. 2024;15:3494.

Salajegheh Tazerji S, Nardini R, Safdar M, Shehata AA, Magalhães Duarte P. An overview of anthropogenic actions as drivers for emerging and re-emerging zoonotic diseases. Pathogens. 2022;11(11):1376.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. Detections of highly pathogenic avian influenza in mammals [internet]. USDA; 2024. Available from: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-detections/mammals

To link to this article - DOI: https://doi.org/10.70253/HLKY2618

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this World EBHC Day Blog, as well as any errors or omissions, are the sole responsibility of the author and do not represent the views of the World EBHC Day Steering Committee, Official Partners or Sponsors; nor does it imply endorsement by the aforementioned parties.

Robyn Alders is an honorary professor with the Development Policy Centre within the Australian National University; an adjunct professor in the Department of Infectious Disease and Global Health, School of Veterinary Medicine, Tufts University; and a senior consulting fellow with the Chatham House Global Health Programme.

Dirk Pfeiffer is Chow Tak Fung Chair Professor of One Health at City University of Hong Kong and professor of veterinary epidemiology at the Royal Veterinary College in London. He is a commissioner with the Lancet-PPATS Commission on the prevention of viral spillover and an investigator with the GCRF One Health Poultry Hub.