Communicating to diverse audiences: what can plain language summaries offer?

Author: Dr Karen Gainey

Health information, either for ourselves or a loved one. Today, the challenge is Introduction: Why did I do a PhD about plain language summaries?

Most of us will have found ourselves searching for health information, either for ourselves or a loved one. Today, the challenge is not a lack of health information; it is working out what health information is reliable and what is not from the overabundant supply. Although the Internet is a popular source of health information, its unregulated nature poses a threat. The sharing of low-quality health information or health information before it is fact-checked can lead to the spread of misinformation and disinformation known to erode public trust in science and evidence-based health care. I saw this myself many years ago as a member of a Facebook group for people with fibromyalgia. Members shared with the group information about non evidence-based therapies, many proven not to work. My PhD was born out of the frustration I felt seeing people let down when these often costly therapies didn’t work.

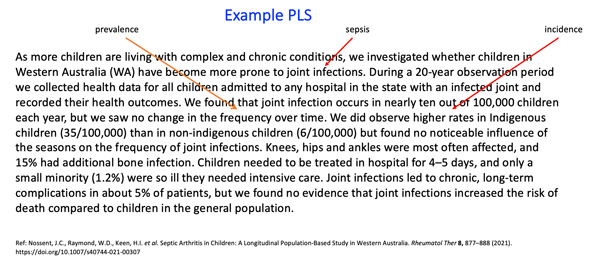

One way we can combat misinformation is by using peer-reviewed health research in a form that is accessible and easy to understand without the need for expert or technical knowledge. Health research is one of the most reliable types of health information; however, it is not always accessible or written with the public in mind. This is where plain language summaries (PLSs) are valuable. They are summaries of research articles written in plain, easy-to-understand language aimed at a non-scientific audience. You might know them by the term lay summaries. PLSs are mainly located in journal articles, and most PLSs are text-only; however some journals offer formats incorporating audio and visual elements, e.g., infographics and podcasts. Although growing in popularity in recent years with journal publishers and researchers, most health and medical journals still do not publish PLSs. PLSs also form part of research funding applications for consumer groups or government agencies. There is no single audience for PLSs; they can benefit many interest holders, including consumers/patients, caregivers, agencies that fund health and medical research (government or private, not for profit), non-specialist researchers, health care practitioners, consumer groups, policymakers and media representatives. Regardless of the audience, the primary function of PLSs is to take technical, scientific health research and communicate it to the reader in a way they can easily understand and use.

Background: PhD overview

My PhD focused on aspects related to the production, publication and dissemination of PLSs in health and medical journals. This involved a review of the author instructions for writing PLSs in health and medical journals, followed by a check of published PLSs to see how closely these guidelines were followed. When PLSs were first introduced, there was no evidence that potential end users were consulted for their feedback. I conducted a qualitative study to help understand what is most important to people who read PLSs, specifically those with chronic medical conditions (because they are high users of health information). Bringing my findings full circle, I interviewed editors and publishers from health and medical journals about barriers and facilitators in the publication and dissemination of PLSs.

These studies yielded some unexpected results, many of which challenged assumptions about PLSs based on the existing literature as well as those held by me and the research team. So let’s dive into them!

The problem: Identifying research gaps and questions.

Although PLSs are a great resource, there is work to be done to improve their effectiveness as a means of communicating health research to a diverse audience. Not all journals publish PLSs, and amongst those that do, many do not make PLSs a mandatory part of the submission process. Journals provide author instructions or guidelines to detail how to write a PLS, however, reviews note that these instructions vary between publishing groups with a high degree of variation. Efforts have been made to standardise PLS guidelines, however, this approach has yet to be evaluated. We also lack an understanding of author adherence to these PLS guidelines. Of concern, studies indicate that PLSs contain high levels of jargon and are frequently written at reading levels higher than is recommended for a general audience. Involving end-users of PLSs in their development could help address this concern. However, despite the clear benefits of such involvement, the extent to which this has been adopted in practice is unclear. Very little is known about the behind-the-scenes aspects at the journal and publisher levels that impact the publication and dissemination of PLSs.

The search for answers: Each study built on the one before it.

What author instructions do health journals provide for writing plain language summaries? A scoping review. Starting with a scoping review, we screened 534 journals and found that only 27 (5.1%) published PLSs. Most (70%) did not require a PLS. There was wide variance in the author instructions between journals, with varying levels of detail. For example, word count or length ranged from 100 to 850 words. Although most (70%) of journals included guidance to avoid jargon, acronyms and abbreviations, only one suggested using a readability tool.

Are plain language summaries published in health journals written according to instructions and health literacy principles? An environmental scan.

To follow up, we checked the compliance of PLSs from the journals in the scoping review and conducted a health literacy assessment on the PLSs. No journal's PLSs achieved 100% compliance. However, two journals achieved a high rating (≥85% compliance). Five journals (20%) achieved low (≤ 50%) or very low (≤ 35%) compliance. The health literacy assessment showed that the mean grade reading level for all PLSs was grade 15.8 (range 10.2–21.2), and the mean percentage of complex words was 31% (range 8.5%–49.8%).

Perspectives of people with chronic illness about plain language summaries: a qualitative analysis.

In the first of two qualitative studies, we asked 19 people from six countries who are familiar with PLSs for their thoughts on what works and suggestions for improvement. We found that people wanted PLSs that contained practical information that they could easily use to help with their treatment decisions. It was also important that PLSs were accessible and written using language that respects the reader. Co-design was seen as important but only if done in a meaningful, not tokenistic way. People wanted their contribution to be valued. Some medical conditions have an impact on the way information is processed, so offering formats in addition to text-based PLSs could be a useful way of reaching more people e.g., podcasts, video summaries and infographics. Participants suggested that some level of medical jargon could be included in PLSs and the reading level could be higher than the usually recommended grade 8.

What do journal editors think about opportunities and barriers in the advancement of the publication of plain language summaries? A qualitative analysis.

The second qualitative study (under review), was conducted with editors and publishers of health and medical journals. Some publishers gave editors more support in terms of resources to help them prioritise the publication of PLSs. For journals, the level of support from publishers varied, as did their autonomy to make decisions. Opinions were mixed on the use of creative formats for PLSs such as video, however editors understood that plain language summaries have a diverse audience e.g., patients/carers, health professionals, researchers and policy makers. however Editors acknowledged that artificial intelligence (AI) could help authors and journals produce more PLSs, but humans are needed to make sure there are no errors.

Challenges/obstacles/lessons learned.

The findings from my PhD highlight the challenges that exist in the field of PLSs. Despite some advancements to help make PLSs more accessible and available, much work must be done to better cater to the diverse audience of PLSs. Journal author instructions for PLSs vary substantially between journals, and researchers' compliance with these instructions is moderate at best. Complicating matters is a lack of governance systems from many journal publishers to manage better quality control and a lack of consensus from editors and publishers about prioritising PLSs for their journals. Support (e.g., clear instructions and advice) for researchers to write PLSs that conform to journal guidelines and health literacy principles is also lacking.

Next steps

Findings from these studies suggest that there is an opportunity to improve the way PLSs are written and published in order to optimise their value as a tool for communicating research findings with a diverse audience. Some steps that we could take to achieve this include:

- The inclusion of a PLS as a requirement by all journals, with the PLS being included in the peer review process.

- A better understanding of the actual readership of PLSs, with an appreciation of the value of non-text based PLS formats.

- Processes to facilitate the input from end-users in PLS development through meaningful co-design, and distribution through avenues such as social media and community-based groups.

Key take home messages

- Plain language summaries (PLSs) provide interest holders with the findings of health and medical research written in a way that is easy for non-experts to understand.

- Many journals publish PLSs with the most common format being text-based; however, formats with audio and visual elements are becoming more popular as they offer the audience more options.

- There is work to be done to make PLSs more effective, and involving end-users in their co-design is a good place to start.

References

Gainey, K.M., Smith, J., McCaffery, K.J, Clifford, S., Muscat, D.M.M. (2023). What author instructions do health journals provide for writing plain language summaries? A scoping review. The Patient. 16, 31–42. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-022-00606-7

Gainey, K.M., Smith, J., McCaffery K., Clifford, S., Muscat, D. (2024). Are plain language summaries published in health journals written according to instructions and health literacy principles? An environmental scan. BMJ Open, 14, e086464. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-086464

Gainey, K,.M., McCaffery, K., & Muscat, D. (2025). Perspectives of people with chronic illness about plain language summaries: a qualitative analysis. Health Promotion International, 40(2). Doi: 10.1093/heapro/daaf044. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40252004/

Haughton M and Machin D. The prevalence and characteristics of lay summaries of published journal articles. Poster presented at: European meeting of the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals; 2017 17-18 January; London United Kingdom. Available from: https://www.costellomedical.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/The-Prevalence-and-Characteristics-of-Lay-Summaries-of-Published-Journal-Articles.pdf

Rosenberg, A., Baróniková, S., Feighery, L., Gattrell, W., Olsen, R.E., Watson, A., (2021). Koder T & Winchester C. Open Pharma recommendations for plain language summaries of peer-reviewed medical journal publications. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 37(11), 2015-2016. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34511020/

Song, M., Elson, J., Nguyen, T., Obasi, S., Pintar, J & Bastola, D. (2024). Exploring trust dynamics in health information systems: the impact of patients’ health conditions on information source preferences. Frontiers in Public Health, 12. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1478502

Stoll, M., Kerwer, M., Lieb, K., & Chassiotis, A. (2022) Plain language summaries: a systematic review of theory, guidelines and empirical research. PLOS One, 17(6):e0268789. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268789

Wada, M., Sixsmith, J., Harwood, G., Cosco, T.D., Fang, M.L., & Sixsmith, A. (2020). A protocol for co-creating research project lay summaries with stakeholders: Guideline development for Canada’s AG-WELL network. Research Involvement and Engagement; 6(22). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-020-00197-3

Wen, J., & Yi, L. (2023). Comparing lay summaries to scientific abstracts for readability and jargon use: a case study. Scientometrics, 128, 5791-5800. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04807-1

Zhang, Y., Sun, Y & Xie, B. (2015). Quality of health information for consumers on the web: A systematic review of indicators, criteria, tools, and evaluation results. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(10), 2071-2084. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23311

The SHeLL Editor is an automated tool that supports the application of health literacy principles to written text: https://www.healthliteracysolutions.com.au/

Cochrane plain language summaries: https://www.cochrane.org/evidence#gsc.tab=0

To link to this article - DOI: https://doi.org/10.70253/RACQ4397

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this World EBHC Day Blog, as well as any errors or omissions, are the sole responsibility of the author and do not represent the views of the World EBHC Day Steering Committee, Official Partners or Sponsors; nor does it imply endorsement by the aforementioned parties.